What Did Luther Ever Do For Us?

– A series reflecting on the influence of Martin Luther on Methodism first published in the Lidgett Park Methodist Church monthly magazine, The Link, in 2017, the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation

by John S. Summerwill

- 1. Who Was Luther?

- 2. Luther and Scripture

- 3. Salvation

- 4. Priests and Sacraments

- 5. Worship

- 6. Hymns and Psalms

- 7. Holiness

- 8. Scripture and Other Authorities

- 9. The Lutheran Legacy

1. Who Was Luther?

The 31st of October is celebrated annually as

Reformation Day by many Protestants, especially Lutherans, commemorating Martin

Luther’s publication of his Ninety Five Theses, which sparked off the

Protestant Reformation. This year it is especially significant as the 500th Anniversary of that event. We Methodists, as Protestants, are heirs of that

Reformation and owe far more of our thinking and practice to Luther than we

often realize. This seems as good a time as any, therefore, to attempt an

assessment of how much we have derived from Luther and also why we Methodists

are not Lutherans. To set the scene, we begin with a very brief outline of

Luther’s life and experience.

The 31st of October is celebrated annually as

Reformation Day by many Protestants, especially Lutherans, commemorating Martin

Luther’s publication of his Ninety Five Theses, which sparked off the

Protestant Reformation. This year it is especially significant as the 500th Anniversary of that event. We Methodists, as Protestants, are heirs of that

Reformation and owe far more of our thinking and practice to Luther than we

often realize. This seems as good a time as any, therefore, to attempt an

assessment of how much we have derived from Luther and also why we Methodists

are not Lutherans. To set the scene, we begin with a very brief outline of

Luther’s life and experience.

Martin Luther was born in 1483 at Eisleben near Leipzig in Saxony-Anhalt, the son of a copper mining entrepreneur, who bought him a good classical education which prepared him for enrolment at the University of Erfurt in 1501. He lived at a hostel that followed monastic rules, studied liberal arts, graduated with excellence and took his master’s degree in 1505. He then started to study law, as his father wanted, but a narrow escape from a lightning bolt in a summer storm so frightened him that he resolved instead to become an Augustinian monk. Intensely diligent, pious and painstakingly obedient to his vows, Luther struggled to find inner peace. He was oppressed by anxieties and melancholy (which persisted throughout his life) and deeply fearful of the majesty and holiness of God.

Luther’s superior selected him to study theology and sent him to Rome, where he was shocked to find a lack of spirituality at the centre of the Church. Back in Saxony he was sent to the Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg, where he completed his doctorate and at the age of 29 became Professor of Biblical Studies at the University of Wittenberg, a post he held for the rest of his life. His preparation for the lectures that he gave on the Psalms, Romans and Galatians took him deeper and deeper into a reconsideration of conventional interpretations and theology, and he began to discover the mercy and love of God. Increasingly he came to believe that the key to all of scripture and to all that matters in Christianity is in the words in Romans 1:17 (and three other places in scripture): ‘The righteous shall live by faith.’ It is by faith that we can receive God’s forgiveness and renewing grace. Luther became increasingly sceptical about the Church’s teaching that grace was conveyed only through the ‘means of grace’, that is, the sacraments and rituals performed by ordained priests.

Luther was not only an academic: he was a preacher and parish priest as well. It was his encounters with ordinary parishioners which led him to see what dreadful damage was caused to people’s spirituality by the sale of indulgences. The Church taught that baptism washes away the original sin that we all inherit, and that penances and the mass bring forgiveness for sins we have committed. Nevertheless, after death we spend a time of suffering in Purgatory before we are fit to be received into heaven. The Church’s authority to forgive sins allowed it to sell indulgences to reduce the length of one’s sentence in Purgatory. When Pope Leo X issued a tranche of indulgences to raise money for the building of St Peter’s in Rome Luther became very concerned that possession of them made people complacent and gave them a false sense of security. He had come to see that God’s forgiveness cannot be bought or earned; it is not in the gift of priests; it is not secured by performing rituals; it is a free gift of grace, which is received by faith alone. So in 1517, when the Dominican itinerant John Tetzel arrived in Wittenberg with indulgences to sell, Luther wrote his ninety five statements of objection and sent them in a letter to the Archbishop of Mainz. (The story of him nailing them to the church door is probably a myth.)

Although it was not originally Luther’s intention to attack the Pope or the authority of the Church, the response he got from them was so hostile that that was what he ended up doing. Over a four-year period Luther had to defend himself on numerous occasions against charges of heresy (an offence usually punished by being burnt alive), first within his own Augustinian order, then before officials in Rome and Augsburg. It was only by the intervention of his Prince, Frederick III (Frederick the Wise), that he escaped arrest and extradition. He wrote a number of books and papers setting out his reasons for holding that the Church had developed ideas and practices that were not consistent with the teaching of the Bible. The Church, he claimed, needed to be reformed and renewed. He attacked the division between ordained and lay members as unbiblical; he wanted to reduce the sacraments to baptism, eucharist and penance; he challenged the doctrine of transubstantiation, thereby threatening the widespread practice of private masses for the souls of the dead; Christians did not need priests and rituals and intermediaries between themselves and God; they could approach God directly and were free to serve God and their neighbours in love. These writings attracted widespread approval from Luther’s growing fan club and caused great irritation to the Establishment, which felt seriously threatened. There was an enormous wave of popular support from those who, wearied with priest-ridden Catholicism, found an exciting spiritual freedom in what seemed to be a return to the purity and simplicity of original Christianity as found in the New Testament. To the Establishment, on the other hand, Luther was a dangerous heretic threatening the very foundations of Christendom by calling into question the authority of Christ’s vicar on earth and the traditions which had accumulated under the Spirit’s guidance. The stakes were very high.

Things came to a head in 1521 at the Parliament in Worms, at which the Holy Roman Emperor himself presided. The Pope had already issued an order excommunicating Luther and ordering that all his books were to be burned. Luther was given a last chance to recant, which he refused, saying :

‘Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God ... I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.’

Luther was fortunate to have the support of Prince Frederick, who had already informed him of a plan to protect him from arrest by a pretended kidnap of him on his way home. For a year Luther went into hiding in Wartburg Castle until the political situation had changed. Frederick was defying the Emperor as well as Rome by defending Luther. The Reformation, however, was never about religion alone. There was a widespread desire among the rulers of the European states for independence from the Holy Roman Empire. Luther was the catalyst for political revolution as well as religious reform. The term ‘Protestant’ was a political term before it became a religious one. It originally referred to rulers of states who protested against the power of the Empire and the Church and wanted freedom to manage their own affairs. When the Reformation broke out the politics and religion were closely intertwined. Over the next century whole states opted in or out of imperial/ecclesiastical control according to the choices of their princes, remaining Catholic or becoming Protestant, with wars and civil wars fought in the intermingled struggles for power and for religious truth and integrity.

During his period in hiding Luther began and completed what was to be the most influential of all his writings—his translation of the New Testament into German. The publication of the Bible in people’s own language, widely disseminated now that printing had been invented, was a hugely significant step in giving lay people personal access to the holy scriptures without the need of a priest.

Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1522, protected by Frederick, and took charge of the reformation that was already under way there prompted by his ideas. Liturgy was changed; people received both bread and wine at the Lord’s Supper; monks were leaving their monasteries and priests were marrying. Luther left the Augustinians in 1524, married a former nun the following year and started a family. He lived to the age of 62, teaching, ministering, lecturing and writing extensively. Although a very learned man, he retained throughout his life something of the roughness of his peasant origins. His table talk and manners were coarse; he could be argumentative and abrasive. Yet he was a humble man and one who genuinely tried to make peace rather than divide the Church. It was his passion for biblical truth that he could not and would not compromise. And it was his own experiences of poverty and powerlessness, of self-loathing and desire to find God, of spiritual renewal through accepting the grace of God by faith, which made him sympathetic to other people’s needs and so imaginative and assiduous in finding ways to make faith come alive for ordinary people.

2. Luther and Scripture

We take our easy access to the Bible so much for granted that we can find it almost impossible to imagine what ignorance of the Bible there was in times when it was available solely in Latin and only priests, monks, nuns and the few rich and well educated people were able to read it. Martin Luther was not the first to give Germans an affordable Bible in their own tongue, but he was the most successful.

Luther was an accomplished Bible scholar long before he discovered salvation by faith. He lived in a period when new approaches to the Bible were bursting on the universities, and he was at the cutting edge of the new scholarship. He had a fluent grasp of Latin, the language in which the Bible was read in the Catholic Church. The Latin Bible, the Vulgate, was defective in many ways because its 4th century author, St Jerome, had used inferior source documents, such as a Greek translation of the Old Testament rather than original Hebrew, he did not always translate correctly, and he brought into his translation questionable interpretations. The Church defended this Vulgate, basing doctrines upon it, and became quite defensive when Renaissance scholars began to criticise its inadequacy and publish German translations in the half century before Luther came on the scene. At a pivotal moment, in 1516 when Luther was lecturing in Wittenberg, the Dutch scholar Erasmus published the first critical edition of the Greek New Testament, drawing upon the best and most ancient manuscripts available. Luther had already mastered Hebrew and begun translating the Old Testament into German. He was joined in the Wittenberg faculty in 1518 by Philip Melanchthon, a Greek scholar. When, therefore, Luther went into hiding during 1521-2 to escape arrest, it is natural that he felt the best use of his time was to translate Erasmus’s New Testament into German, and he did so at an astonishing pace, completing the whole in eleven weeks at a rate of about eleven pages a day, consulting secretly with Melanchthon throughout. The first copies went on sale in 1522 at about half a guilder a copy, the weekly earnings of a young tradesman. Within a couple of years, with the help of colleagues he completed the Old Testament as well, and the books of the Apocrypha too.

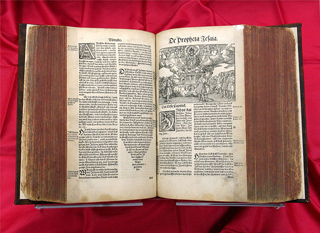

Luther’s

Bible was published in many editions, printed by several different printers. It

was an enormous success in every way. Physically it was attractive because it

was illustrated by superb drawings done by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Luther’s

prefaces and comments, politically charged as they were with criticism of the

papal church, made a sensation. It was a novelty for people to have the Bible

itself in language they could understand, bringing with it a new wave of

spirituality. Above all, Luther’s translation was not dry and academic but

thoroughly ‘modern’ (for its time). He used the principle of translation that

today is called ‘dynamic equivalence’. It means that instead of translating

word-for-word you take a sentence as a whole and think, ‘what would an ordinary

person say to express the same idea in colloquial language?’ To take an

example, the words of the angel to Mary in Luke 1:28 are usually rendered as

‘Hail Mary, full of grace.’ Luther refused to use the word ‘full’ because in

German it is linked with beer or money; and ‘hail’ is not the way normal

Germans would greet anyone. So Luther translates it as Gott grüsse dich, liebe Maria, du holdselige’, which in

English would be something like, ‘God greet you (=hello), dear Mary, thou (intimate ‘you’) gracious

one.’ This is the method used in the Good News Bible and other modern versions.

Luther’s

Bible was published in many editions, printed by several different printers. It

was an enormous success in every way. Physically it was attractive because it

was illustrated by superb drawings done by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Luther’s

prefaces and comments, politically charged as they were with criticism of the

papal church, made a sensation. It was a novelty for people to have the Bible

itself in language they could understand, bringing with it a new wave of

spirituality. Above all, Luther’s translation was not dry and academic but

thoroughly ‘modern’ (for its time). He used the principle of translation that

today is called ‘dynamic equivalence’. It means that instead of translating

word-for-word you take a sentence as a whole and think, ‘what would an ordinary

person say to express the same idea in colloquial language?’ To take an

example, the words of the angel to Mary in Luke 1:28 are usually rendered as

‘Hail Mary, full of grace.’ Luther refused to use the word ‘full’ because in

German it is linked with beer or money; and ‘hail’ is not the way normal

Germans would greet anyone. So Luther translates it as Gott grüsse dich, liebe Maria, du holdselige’, which in

English would be something like, ‘God greet you (=hello), dear Mary, thou (intimate ‘you’) gracious

one.’ This is the method used in the Good News Bible and other modern versions.

Luther’s Bible not only became the standard, popular version in Germany: it shaped the German language itself, playing the same seminal role in Germany as the King James Bible (the Authorised Version) did later in the English-speaking world. Both were translations that have endeared themselves because of their outstanding literary qualities, turning prose into poetry. Musical composers found it easy to pick up the rhythms in Luther’s translation when setting words to music and liked the alliteration in lines like Matthew 5:16, ‘Also lasset euer Licht leuchten vor den Menschen’ (‘Thus let your light shine before all people’).

As a translator Luther approached his task with a fundamental principle that was and is controversial: he was unashamedly a critic, commentator and interpreter, not just a translator. He believed passionately that the heart of the gospel is the good news of salvation by faith in Christ, and therefore judged the importance of the various books of the Bible by the extent to which they reflected this, rearranging them in a different order from that in ancient Bibles to place at the end books of which he took a dim view. These included Hebrews, James (‘an epistle of straw’ saying little about Christ), Jude and Revelation (about which he said he could in no way detect that the Holy Spirit had produced it). He separated out into the Apocrypha the Old Testament books that he did not consider as Holy Scripture (though still worth reading). He thus created a precedent followed later in the English Bible so that what Protestants and Catholics call the Bible is not the same collection of books, or in the same order, let alone the same translation.

Luther’s most radical innovation in relation to the Bible was to make it not just one authority for Christians but the ONLY authority, replacing the Pope, the Church and the whole tradition of theology. This was because he discovered that the study, reading and preaching of the word had a sort of sacramental effect that changed people and situations, speaking to the heart, mind and soul. God has not spoken only to those who wrote the scriptures: he speaks still through them directly to believers.

Initially Luther accepted the ancient understanding, still widely held today, that words are signs or symbols that refer to objects or emotions and not the reality itself. His great discovery in 1518 came first through reflecting on the sacrament of penance, where the words ‘I absolve you of your sins’ are not just a wish or a prayer: they are a speech-act which brings about a real change in the relationship between the priest and the penitent and in the relationship between the penitent and God. In the same way baptism and the Lord’s Supper are based on words of promise that transform those who believe them when they are spoken. Luther saw the whole Bible as a book of God’s promises, which bring us freedom and certainty.

We do not depend [for salvation] on our own strength, conscience, experience, person or works but depend on that which is outside ourselves, that is, on the promise and truth of God, which cannot deceive.

For this is our assurance and defiance ... that God wishes to be our Father, forgive us our sin, and bestow everlasting life on us.

Luther’s placing of the Bible at the centre of Protestantism has had an incalculable impact upon the western world, shaping its culture and perspectives, its values and its politics. He set a standard for translation that others later sought to emulate. The Wesleys grew up in a Protestant church that took for granted that scripture was the primary means by which God speaks to people, and that worship should be focused on the word read and preached. That was what they taught too. Charles Wesley’s hymns are sometimes ‘dynamic equivalence’ translations of passages of scripture (e.g. his version of Psalm 23, ‘Jesus the good Shepherd is’, HP 263) and more often collages or tapestries composed of a multitude of scriptural words or allusions. ‘O thou who camest from above (HP 747, StF564), for example, contains in its sixteen lines ten scriptural references drawn from nine biblical books! Charles was so soaked in his Bible that he naturally thought and prayed in its words.

When the various branches of Methodism united in 1932 to form The Methodist Church as we know it today, they based our doctrine on the revelation recorded in scripture as The Deed of Union states:

The doctrines of the evangelical faith which Methodism has held from the beginning and still holds are based upon the divine revelation recorded in the Holy Scriptures. The Methodist Church acknowledges this revelation as the supreme rule of faith and practice.

We, the fortunate heirs of both Luther and the Wesleys, have inherited their focus on the scriptures in defining our beliefs, clarifing our values, determining our actions, shaping our forms of worship and inspiring our hymnody. In a later article in this series I shall look at ways in which Methodism disagrees with some of Luther’s views on scripture, particularly as the only authority. For now, let us celebrate Luther by giving thanks, as he would, for the Bible, its influence in our lives and our free access to it.

3. Salvation

There is a striking similarity in the experiences of the three most influential shapers of Methodist thinking about salvation, namely St

Paul, Martin Luther and John Wesley. All three were eager, pious, devout,

sincere, diligent men who tried desperately hard to find peace of mind and soul

by meticulous observance of God’s laws and commandments as found in scripture.

All of them failed in their endeavour until they discovered for themselves that

divine grace cannot be earned; it is God’s free gift to the undeserving; it is

by grace alone that we are saved, and that grace is received by faith, i.e.

believe it and you will possess it. All three found a personal relationship

with the living Christ. For all three ‘the gospel’ is the good news that

Christ’s death and resurrection have won a salvation that can put us right with

God regardless of the evil we may have done, and that salvation is now and for

eternity.

There is a striking similarity in the experiences of the three most influential shapers of Methodist thinking about salvation, namely St

Paul, Martin Luther and John Wesley. All three were eager, pious, devout,

sincere, diligent men who tried desperately hard to find peace of mind and soul

by meticulous observance of God’s laws and commandments as found in scripture.

All of them failed in their endeavour until they discovered for themselves that

divine grace cannot be earned; it is God’s free gift to the undeserving; it is

by grace alone that we are saved, and that grace is received by faith, i.e.

believe it and you will possess it. All three found a personal relationship

with the living Christ. For all three ‘the gospel’ is the good news that

Christ’s death and resurrection have won a salvation that can put us right with

God regardless of the evil we may have done, and that salvation is now and for

eternity.

Before Luther made this discovery he was oppressed by the sense that the righteousness of God means that God was justly condemning him, and his perception of Christ was as a judge. What he came to see is that the righteousness of God meant that God loved him and willed his good, and Christ was the saviour with whom he could have a personal relationship. Once we accept God’s forgiveness by faith in Christ, Christ’s righteousness becomes a garment wrapped around us, and God treats us as though we had not sinned. This salvation brings freedom from guilty feelings, power to resist temptation and a confident hope of a future beyond the grave in heaven. What grounds are there for believing it? Because God has made promises in the scriptures, and God is faithful. Luther’s stance was always grounded in scripture.

Luther saw faith and works as inseparable. Faith comes first as a gift from God, and those who have faith naturally and joyously do good works.

Faith is a work of God in us, which changes us and brings us to birth anew from God (cf. John 1). It kills the old Adam, makes us completely different people in heart, mind, senses, and all our powers, and brings the Holy Spirit with it. What a living, creative, active powerful thing is faith! It is impossible that faith ever stop doing good. Faith doesn't ask whether good works are to be done, but, before it is asked, it has done them. It is always active. This kind of trust in and knowledge of God's grace makes a person joyful, confident, and happy with regard to God and all creatures. - Luther’s Commentary on Romans

This understanding of salvation as something very personal and individual has been one of the distinctive marks of Protestantism in general and of Methodism in particular. The Wesleys were driven in their evangelistic mission by the belief that those who died unredeemed would perish for ever; that those who repented and put faith in Christ would be given eternal life; that the task of the Church, therefore, was to save souls by preaching this gospel at every opportunity; that salvation brought freedom and joy into people’s lives. Charles Wesley’s hymns return again and again to this personal experience of seeking and rejoicing in salvation by faith in Christ. And what ‘faith’ means in Protestantism is not what Catholicism understood it to be. It is not the believing of specific doctrines such as those set out in the creeds: it is a personal trust in Christ and in the promises of God in scripture. All this is very Lutheran, though it came to the Wesleys indirectly via the Moravian missionaries they met during their own mission to Georgia in 1735 and subsequently in London. The Moravian Brethren were Protestants even before Luther, tracing their origins to Jan Hus, the 15th century Czech reformer and martyr. The confident trust in God of the Moravian families who travelled with John and Charles Wesley on a stormy voyage across the Atlantic made such a deep impression that neither could rest afterwards until they had found the same faith.

The word ‘evangelical’ came to be associated with this message of personal salvation, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was claimed by both Lutherans and Methodists. Evangelical faith suffered its first serious blows in the late Victorian period when the new methods of biblical criticisms coming from Germany challenged the accuracy and inspiration of the Bible, particularly undermining the concepts of Hell and eternal damnation. Were miracles credible? Could people enlightened by science still believe in virgin birth, resurrection, the deity of Christ, the existence of a heaven with harps and angels? And why bother to try to believe them if it didn’t make any difference now or after your death?

The evangelicalism of Methodism changed greatly during the 20th century as scepticism about much of the Bible and the traditional message spread both outside and instead the Church.

When theology began to be informed by psychology and sociology, and began to understand the techniques of propaganda used by the Nazis and others to such devastating effect, attempts to brainwash people into Christian faith became very suspect, and Methodism increasingly drew back both from the individual buttonholing approach used by Jehovah’s Witnesses and from the big rally approach of Billy Graham. Maybe the Church would be more effective, more honest, less manipulative, it was thought, by focusing on the ‘social gospel’, demonstrating faith in practice by feeding the hungry, caring for the needy, campaigning for justice and peace. ‘Preach Christ, using words if necessary’ was one slogan.

The ecumenical movement had a major impact too, especially after the new reformation that happened within the Catholic Church in the 1960s. Methodists, along with other Protestants, have rediscovered some of the Catholic perspectives they had partly lost. Among them is the recognition that salvation is as much a process as an event; we change and develop over time, influenced by others, by our environment and our experiences; we regress as well as advance; we need the community of the church, and specialist ministries; we are helped by rituals, sacraments and other ‘means of grace’ as long as we do not make them ends in themselves; and salvation is needed by communities as well as individuals; we have a social responsibility to bring healing, justice and peace to the world. None of these notes has ever been absent from Methodism, which has always had a social as well as personal dimension. They have, though, been more loudly sounded in the last half century. Some welcome the broader understanding of salvation: others think that the loss of focus on challenging individuals about their own salvation has been the root cause of the church’s contraction.

It is difficult to say how much of Luther’s doctrine of salvation is still central to Methodism now. What Methodism today means by ‘the gospel’ is more than Luther meant by it, and it is questionable whether either Luther or the Wesleys would think that modern Methodism is ‘evangelical’ as they would understand the term. But we cannot say, simplistically, that the church today would thrive if only we went back to preaching what they preached, using their methods. They were modern men in their generation, scholars at the cutting edge, using their knowledge and understanding to address the world as they found it and sweeping away legacies that were not useful any more. They might think us not nearly radical enough.

4. Priests and Sacraments

The Catholic Church in Luther’s

day had (and still has) seven sacraments: baptism,

confirmation, the mass, penance, anointing of the sick, ordination, and

matrimony. Bishops perform confirmations and ordinations: the others

(except baptism) are valid only if performed by a Catholic priest, who must

himself have been ordained by a Catholic bishop. Luther’s reflections on what

he saw as the corrupt nature of the Church in his day led him to the conviction

that the power of the priestly hierarchy, and the wealth that went with it, were

unscriptural and wrong, and that the only true sacraments were those commanded

by Jesus. Good priests might help people to come to saving faith: priesthood

itself, though, was often a barrier to faith because people wrongly thought

that only priests could come near to God, and their monopoly of the sacraments

gave them too much power to interfere in the lives of their flock.

The Catholic Church in Luther’s

day had (and still has) seven sacraments: baptism,

confirmation, the mass, penance, anointing of the sick, ordination, and

matrimony. Bishops perform confirmations and ordinations: the others

(except baptism) are valid only if performed by a Catholic priest, who must

himself have been ordained by a Catholic bishop. Luther’s reflections on what

he saw as the corrupt nature of the Church in his day led him to the conviction

that the power of the priestly hierarchy, and the wealth that went with it, were

unscriptural and wrong, and that the only true sacraments were those commanded

by Jesus. Good priests might help people to come to saving faith: priesthood

itself, though, was often a barrier to faith because people wrongly thought

that only priests could come near to God, and their monopoly of the sacraments

gave them too much power to interfere in the lives of their flock.

To call

popes, bishops, priests, monks and nuns the religious class, but princes,

lords, artisans and farm-workers the secular class is but a specious device

invented by certain time-servers. But no-one ought to be frightened by it, and

for good reason. For all Christians whatsoever really and truly belong to the

religious class and there is no difference among them except in so far as they

do different work ... For baptism, gospel and faith alone make men religious

and create a Christian people ... The fact is that our baptism consecrates us

all without exception and makes us all priests (I Peter 2:9, Revelation

5:9-10).

—Appeal to the German Ruling Class

Thus Luther taught ‘the priesthood of all believers’. He held that there is no ceremony or task for a priest or bishop that could not performed by any baptised Christian. He rejected altogether the idea that in ordination God changes someone’s status indelibly, seeing it as only the church authorising someone to fulfil a task:

There is no other Word of God than that which is given all Christians to proclaim. There is no other baptism than the one which any Christian can bestow. There is no other remembrance of the Lord’s Supper than that which any Christian can observe and which Christ has instituted. There is no other kind of sin than that which any Christian can bind or loose.’ —Concerning the Ministry

Luther believed the key role of priests and bishops is to preach the Word. He recognised that there is a need for trained ministers and that different people have different callings and talents. In practical terms, therefore, it remains desirable to have qualified pastors and overseers, who should be chosen by the church communities they lead.

One important consequence was that he saw no continued need for the so-called ‘religious’ to be celibate or to cut themselves off from the world in monasteries and nunneries. One could be a minister and live a normal married life, as he chose for himself.

All this is familiar to Methodists, for our own understanding of the status and role of our ordained ministers is fully in line with Luther’s. Like him, we regard the hierarchy of offices from deacon to pope via bishops, cardinals and others as an unnecessary, unbiblical and essentially worldly construction. We see ministers as different from lay members of the church in their vocation and role, not in their status. Normally they baptise, preside at Holy Communion, conduct weddings and funerals, make pastoral visits, etc., but all of these can be done by lay members, though it requires authorisation from Conference to preside at Communion and, for legal reasons, only an authorised celebrant may conduct a marriage ceremony. In this we occupy a sort of middle ground, not eliminating ordained ministry altogether like the Quakers and some independent churches, nor following the Catholic episcopal tradition like the Anglicans. Our superintendents and district chairs are different from other presbyters only in the work they do: they are not members of a higher order of ministry; they lose their title when they retire or resign. The greater part of Methodist worship is led by local preachers, who are trained and commissioned for their church work yet earn their living in secular occupations.

Outside Britain some Methodist Churches have bishops: attempts to introduce episcopacy here have always met stiff opposition based on ‘the priesthood of all believers’ and a visceral distaste, like Luther’s, for the trappings of power.

Only two of the seven sacraments were, he claimed, commanded by the Lord in scripture and therefore to be treated as effectual sacred rites—baptism and the eucharist. (He was rather ambiguous about penance, sometimes calling it a sacrament, sometimes not. It had a part to play in early Methodism, in that Wesley’s most committed followers formed themselves into ‘bands’, close-knit groups who met to share a private spiritual intimacy. It is lost from Methodism now. )

Luther reinterpreted the eucharist in a radically different way from Catholic tradition. Catholicism saw the Mass as a re-enactment of the sacrifice of Jesus (hence the use of an ‘altar’ and a priest) and held that the bread and wine, when properly consecrated, were changed into the actual body and blood of Christ by transubstantiation. This gave rise to superstitious beliefs about their efficacy, and for various reasons worshippers other than the priest were allowed to receive only the bread, not the wine (called ‘communion in one kind’). Many medieval priests made a living out of saying daily mass for the souls of rich benefactors who endowed chantry chapels so that the masses said for them would reduce their time in Purgatory and speed their path to heaven. All this Luther swept away. The sacrifice of Christ was made once for all on the cross: it never needs to be repeated, so no altar or priest is required. The only sacrifice needed now is the sacrifice of our souls and bodies to Christ (Romans 12:1). The bread and wine remain bread and wine: there is no magical transformation in them. However, unlike the more radical Swiss Protestant, Zwingli, Luther did not think that the eucharist was merely a memorial of what happened at the Last Supper. He taught the ‘real presence’ of Christ, who is with us always and particularly when the Christian community gathers at his table. Worshippers were to receive both bread and wine, as scripture commands. What makes the Lord’s Supper a sacrament, a means of grace, is not the ritual, nor the status of the person who presides, but the faith of those who participate and their spiritual union with Christ.

The most revolutionary feature of Lutheran eucharists was that they were in common German, not the traditional Latin. Luther wanted to involve people in active participation in worship, so using the vernacular language removed another barrier, another distinction between priest and people. All this, too, we Methodists can recognise as our inheritance from Luther.

On the whole Methodism has been content with Luther’s view of the ministry, though not all Methodists understand the difference between ministers and priests. There are times when people want ministry that they can believe is divinely empowered, especially when they need assurance of forgiveness, or healing, or a blessing in time of danger, or the certainty that their marriage is made in heaven. Catholic and Anglican priests may have an easier time than Methodist ministers in being treated as persons who carry such authority: it is inherent in their office. Some Methodists do regard ordained ministers as priests, and some ministers think of themselves in that way. For others, though, ministers are no different from anyone else except in the job they do.

Methodists would not take at all easily to the demand for obedience that the Catholic Church requires, especially when a celibate male clergy seems so out-of-touch with the membership in matters of gender equality and sexual ethics. Ecumenical progress hits a barrier when Methodists refuse to accept that our ministers need to be reordained by a bishop or that priests alone can perform valid sacraments. Some will say that it is time for the Methodist minority to give in and rejoin the mainstream within the traditions of Anglican and Catholic ministry for the sake of the unity of the Church. Others will say that Luther was right: it would be foolish to give up our freedoms and revert to an unbiblical, irrational, semi-magical understanding of church leadership. I’m with Luther on that.

5. Worship

Picture: Luther leading family worship, by G.A.

Spangenberg (19th cent)

Picture: Luther leading family worship, by G.A.

Spangenberg (19th cent)

The word ‘liturgy’ means ‘work of the people’. One of Luther’s chief complaints about liturgical worship was that it had been taken from the people and become the preserve of the clergy. To restore it to the people, he translated the liturgy into German, gave the people more parts to say, encouraged congregational singing and allowed communicants to receive both the bread and the wine at Communion.

Luther published a number of books about worship, including guidance on public services and private devotion. Their contents are too vast and complex to cover in a short article like this, and his views changed over time, so there was never one definitive statement from him about how worship should be ordered. I can only summarise some key features.

In the Catholic churches and monasteries of Luther’s time mass was said daily and priests observed the seven daily offices, all in Latin. At mass the scriptures were read in Latin, which the laity did not understand, and there was little preaching. Luther complained:

Three serious abuses have crept into the service. First, God's Word has been silenced, and only reading and singing remain in the churches. This is the worst abuse. Second, when God's Word has been silenced such a host of un-Christian fables and lies, in legends, hymns, and sermons were introduced that it is horrible to see. Third, such divine service was performed as a work whereby God's grace and salvation might be won. As a result, faith disappeared and everyone pressed to enter the priesthood, convents, and monasteries, and to build churches and endow them. — Concerning the Order of Public Worship

The principles that guided Luther in his reform of worship were three:

- All liturgical elements that are contrary to the teachings of scripture should be eliminated.

- All those elements that are commanded by God in scripture should be retained.

- Those things that are neither commanded nor forbidden are considered adiaphora (‘things indifferent’).

Following the first of these principles, Luther opposed the unscriptural veneration of saints and strenuously objected to the practice of praying to saints to intercede with God on our behalf. Christ is the only mediator with the Father that we need. Luther therefore abolished the celebration of saints’ days and greatly simplified the calendar of festivals, arguing that myths about saints had distracted Christians from the pure word of God. Prayers to saints and to the Virgin Mary were abolished, as were prayers for the dead and for the Pope.

The second principle led to much more focus on scripture, including both more use of psalms and of preaching. Latin continued to be used for well known hymns like the Te Deum and the Sanctus, but Bible readings and preaching in German made the worship more intelligible.

Luther simplified the daily offices, reducing them to two—morning and evening prayers — each including Bible reading and exposition as well as hymns, psalms and prayers. They were not to go on for more than an hour, so as not to weary people. (‘Three cheers for that’, you say, but he also said that the reading and preaching should be half an hour!) He did not expect lay people to attend except on Sundays, when the eucharist—with a sermon— was to remain the principal act of worship.

The third principle led Luther to be easy-going about traditions like clerical garb, incense and images.

Images, bells, Eucharistic vestments, church ornaments, altar lights, and the like I regard as things indifferent. Anyone who wishes may omit them. Images or pictures taken from the Scriptures and from good histories, however, I consider very useful yet indifferent and optional. I have no sympathy with the iconoclasts. - Martin Luther's Basic Theological Writings

In his Small Catechism Luther provides a simple form of morning prayer for family use as follows:

In the

morning, when you rise, you shall bless yourself with the holy cross and say:

In the name of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Then, kneeling or standing, repeat the Creed and the Lord's Prayer. If you

choose, you may, in addition, say this little prayer:

I thank you, Heavenly Father, through Jesus Christ, your dear Son, that you

have kept me this night from all harm and danger; and I pray you to keep me

this day also from sin and all evil, that all my doings and life may please you.

For into your hands I commend myself, my body and soul, and all things. Let your

holy angel be with me, that the Wicked Foe may have no power over me. Amen.

Then go to your work with joy, singing a hymn, such as the Ten Commandments, or

what your devotion may suggest.

There is a similar pattern for evening prayer, and short graces to say before and after meals.

From a Methodist perspective, none of this is very strange. We may be a little surprised to find Luther so conservative in holding on to Latin hymns and Catholic practices that cause English Protestant heads to shake, like crucifixes and crossing oneself: the English Reformation followed the more radical Calvin, who taught that worship should contain only what scripture commanded and explicitly approved. However, it is no surprise to us that worship should be simple, in plain language, centred around the reading and preaching of the word, with plenty of congregational participation in the singing. That’s what we do. And it’s thanks to Luther that we do, for without the reforms he instituted we might still be following the worship practices of medieval Catholicism. Of course, the Catholic Church itself has changed as well. It did reform itself after Luther and again, radically, in the 1960s after Vatican II. The ecumenical Liturgical Movement since the 1970s has brought the worship of the different denominations ever closer and enabled us to worship together in ways that were not possible before the healing of the rift in the late 20th century.

One significant difference in our practice is that we do not celebrate Holy Communion every Sunday. That is a hangover from the Calvinistic nature of the English Reformation, which made Communion a rare event to increase its solemnity and importance. John Wesley encouraged weekly communion without much success, and the Methodist Sacramental Fellowship campaigned from the 1930s onwards for more frequent communion, making little headway until the Liturgical Movement changed ministerial thinking and made communion more frequent and more accessible. Even if the will existed for Methodists to receive communion weekly we would be unable to staff it unless more local preachers were authorised to celebrate.

There are, perhaps, some lessons from Luther that we have forgotten. He was wise enough to value the core elements of eucharistic worship that could be traced back to biblical times and to the early church and he kept familiar features of worship that people knew and loved as long as they were not inconsistent with scripture. He had no sympathy with those who would sweep away all that was old just because it was old. The basic structure of the Lutheran liturgy and its key elements would be recognisable to Catholics of every period. Some of us feel at times today that the Methodist Church is no longer the church we joined. We find it difficult to recognise some of its liturgy, its worship practices and its hymns. Important as it is that the Church and its worship are relevant to the times in which we live, it is vital too that we maintain continuity with our Christian ancestors, and sustain our faith by drinking from the same well as they did, or else we lose our Christian identity. Particularly we stand in danger of losing—if we haven’t already lost—our sense of the holiness of the house of God and of the sacred mystery that we come to encounter there. Without that, there is no worship, only empty ritual and entertainment.

I hope that the celebration of Luther’s quincentenary will renew our sense of the preciousness and worth of our inheritance.

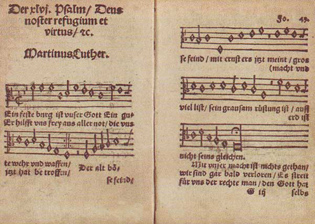

6. Hymns and Psalms

‘Methodism was born in song’,

says the Introduction to The Methodist

Hymn Book (1933): and still we love congregational singing. The same could

be said of the Protestant Reformation, for one of Luther’s greatest gifts to

the Church was to encourage hymn-singing, himself writing and publishing both

hymns and tunes. Yet he was not the first to do so within the Reformation. A

couple of decades earlier, in 1501, the Bohemian Brethren (also known as the

Moravians) published their first hymn book, containing 89 hymns. In Catholic churches priests or choirs

sang plainsong hymns in Latin: in the Moravian Church everyone could join in

singing ‘modern’ hymns in their native German.

‘Methodism was born in song’,

says the Introduction to The Methodist

Hymn Book (1933): and still we love congregational singing. The same could

be said of the Protestant Reformation, for one of Luther’s greatest gifts to

the Church was to encourage hymn-singing, himself writing and publishing both

hymns and tunes. Yet he was not the first to do so within the Reformation. A

couple of decades earlier, in 1501, the Bohemian Brethren (also known as the

Moravians) published their first hymn book, containing 89 hymns. In Catholic churches priests or choirs

sang plainsong hymns in Latin: in the Moravian Church everyone could join in

singing ‘modern’ hymns in their native German.

Whether Luther got the idea from the Moravians, I do not know. What he did was essentially the same and for the same reasons. Making worship accessible by using the vernacular, and encouraging full participation by everyone, gave real meaning to that phrase ‘the priesthood of all believers.’

Luther included among his many talents and accomplishments a gift for writing verse and for composing and performing music. The foundations were laid in his schooldays at Eisenach, where the curriculum included four hours a week of music. He sang with a pleasant tenor voice in the St George’s Church Choir and played both the lute and the flute. As a monk he became proficient in singing the plainsong hymns, psalms and liturgy. He drew on that inheritance and developed it to make it accessible to others without his training, for he loved music and thought of it as a great gift of God to be used in God’s service.

Next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world. It controls our thoughts, minds, hearts, and spirits ... We marvel when we hear music in which one voice sings a simple melody, while three, four, or five other voices play and trip lustily around the voice that sings its simple melody and adorn this simple melody wonderfully with artistic musical effects, thus reminding us of a heavenly dance, where all meet in a spirit of friendliness, caress and embrace.

A person who gives this some thought and yet does not regard music as a marvellous creation of God, must be a clodhopper indeed and does not deserve to be called a human being; he should be permitted to hear nothing but the braying of asses and the grunting of hogs.’ - Foreword to Georg Rhau's Collection Symphoniae iucundae, 1538

Luther himself wrote 42 hymns on a wide range of themes. There were hymns for all of the major seasons and festivals of the church year; for communion, baptisms and funerals; settings of the creed, commandments, Lord’s Prayer and liturgical passages like the Sanctus; several psalms. They express a confession of faith rather than personal feelings, and are written in plain, simple language with regular metrical form to make them easy to sing. Wherever his basis was an existing text he expanded and transformed it rather than write a mere paraphrase in verse. He published the first of them within four years of the start of the Reformation and added more later in conjunction with the poet and composer Johann Walter. The tunes came from many sources: adaptations of Gregorian chants, Latin Office hymns, German religious folksongs, secular folk tunes and original tunes modelled in the character of German folk tunes. They were immediately popular and were widely sung in homes and secular gatherings as well as in church services. Out of them there developed that most characteristic of Lutheran musical styles, the harmonised chorale, which Johann Sebastian Bach would later perfect so sublimely.

Luther was not only a hymn composer himself: he encouraged a hymn revolution.

I also wish that we had as many songs as possible in the vernacular which the people could sing during mass, immediately after the gradual and also after the Sanctus and Agnus Dei. For who doubts that originally all the people sang these which now only the choir sings or responds to while the bishop is consecrating? ... But poets are wanting among us, or not yet known, who could compose evangelical and spiritual songs, as Paul calls them (Col. 3:16), worthy to be used in the church of God ... I mention this to encourage any German poets to compose evangelical hymns for us. - Preface to Formulae Missae (1523)

Following Luther’s lead, hundreds of hymn texts were translated into German or written anew. Nearly 100 hymnals were produced by the time of his death in 1546. None of this would have been possible, of course, without the movable type printing press invented by Gutenburg in the previous century. Wittenburg had several printing houses by the time Luther needed them for his many books, including his German Bible and the hymn collections. Luther knew and exploited to the full the power of the printed word; so, later, did John Wesley.

As Methodists we are indebted to Luther for giving us one of the most treasured elements in our worship. Yet it was not directly from Luther that it came. The English Reformation, following Calvin, was reluctant to allow any congregational singing other than psalms or metrical psalms, which dominated throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. It was the Congregationalist Isaac Watts who first broke away from a slavish paraphrasing of psalms to making ‘David sing like Christian’ by using biblical texts as a jumping off point for more imaginative writing. The Wesleys admired Watts’ work; Susanna used to sing his hymns with her children in the kitchen at Epworth. John was hugely impressed by the hymns of the Moravian missionaries with whom he shared a voyage to Georgia and translated and published 33 of them soon after his arrival there (having learnt German during the journey, partly from the hymns themselves!). When in 1738 Charles then John had their conversion experiences and wanted to sing about them, the pattern was there for them already. Charles wrote original hymns: John edited hymns and collected melodies (—like Luther, he was a flautist). Both published often, and John compiled the definitive collection of 1780, Hymns for the Use of the People Called Methodists. (Curiously, John’s hymns were all written before his conversion, Charles’s afterwards.) Like Luther the Wesleys were happy to use secular tunes and to let the popularity of hymn singing be the means by which the gospel message could be fixed in people’s hearts and minds. ‘Whoever sings prays twice’, as St Augustine said. We remember better words that we sing, and their significance for us grows as we sing them vigorously with others. When a hymn allows us to put thoughts and feelings into words better than we could ourselves devise, and a good tune carries it, the hymn becomes a prayer, a blessing, a means of grace.

Many of Luther’s hymns are still in use in Lutheran churches. They were almost unknown in England until a romantic interest in antiquity in the 19th century led to a fashion for translations of poems from olden days. We in Methodism now know only these:

A safe stronghold our God is still (Psalm 46), translated by Thomas Carlyle, and sung to Luther’s own tune Ein Feste Burg (HP 661 StF 623)

Out of the depths I cry to thee (Psalm 130), translated by the brilliant Unitarian champion of women’s education Catherine Winkworth (who deserves an article all to herself), and sung to the fine Victorian chorale-like tune St Martin (HP429 StF 433)

Luther’s lovely Christmas hymn in Hymns and Psalms (100) From heaven above to earth I come to his tune Von Himmel Hoch has, alas, dropped out of use.

The old Methodist Hymnbook also had Luther’s fine Easter hymn Christ Jesus lay in death’s strong bands set to his tune Christ Lag in Todebanden (MHB 210).

Christ Jesus

lay in death’s strong bands

For our

offences given;

But now at

God’s right hand he stands,

And brings us life from heaven:

Wherefore

let us joyful be,

And sing to

God right thankfully

Loud songs

of Hallelujah!

Hallelujah!

7. Holiness

If there one doctrine that is distinctively Wesleyan it is the Wesleys’

concept of holiness, variously called

Scriptural Holiness, Sanctification, Christian Perfection or Perfect Love. Most

Christian traditions see holiness as other-worldliness or mysticism and

something reserved for a minority of special people: the Wesleys

saw it as the ordinary way of life for every Christian who loves God and

neighbour and produces the fruit of the Spirit. This is probably the biggest

point of difference between Methodism and Lutheranism, for Luther thought it

was impossible for anyone ever to be truly righteous in God’s eyes, even those

justified by faith. In his view, God treats the redeemed as righteous even

though they are not. Wesley was appalled at the idea that God would pretend, or

demand of us a perfection that is impossible. In this he thought Luther was

wrong-headed and unscriptural, for scripture clearly says in 1 John that God’s

children do not sin, and in Galatians that all who

possess the Spirit of God are the children of God. Luther tried to resolve the

tension between Law and Gospel by saying that the Gospel abolishes the Law.

Wesley resolved it by claiming that the Law is a burden only when we are servants

of God trying unsuccessfully to do our duty; when God’s spirit in our hearts

assures us that we are the children of God his commands are no longer a burden

but a delight. Our imperfection, immaturity and ignorance are not sin: it is wilful

If there one doctrine that is distinctively Wesleyan it is the Wesleys’

concept of holiness, variously called

Scriptural Holiness, Sanctification, Christian Perfection or Perfect Love. Most

Christian traditions see holiness as other-worldliness or mysticism and

something reserved for a minority of special people: the Wesleys

saw it as the ordinary way of life for every Christian who loves God and

neighbour and produces the fruit of the Spirit. This is probably the biggest

point of difference between Methodism and Lutheranism, for Luther thought it

was impossible for anyone ever to be truly righteous in God’s eyes, even those

justified by faith. In his view, God treats the redeemed as righteous even

though they are not. Wesley was appalled at the idea that God would pretend, or

demand of us a perfection that is impossible. In this he thought Luther was

wrong-headed and unscriptural, for scripture clearly says in 1 John that God’s

children do not sin, and in Galatians that all who

possess the Spirit of God are the children of God. Luther tried to resolve the

tension between Law and Gospel by saying that the Gospel abolishes the Law.

Wesley resolved it by claiming that the Law is a burden only when we are servants

of God trying unsuccessfully to do our duty; when God’s spirit in our hearts

assures us that we are the children of God his commands are no longer a burden

but a delight. Our imperfection, immaturity and ignorance are not sin: it is wilful

John Wesley’s experience of feeling his heart ‘strangely warmed’ occurred at a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street where, as he says in his Journal, ‘one was reading Luther’s Preface to the Epistle to the Romans.’ Wesley was initially well disposed towards Luther, appreciating his focus on grace, on faith and on the possibility of instantaneous conversion. He was also deeply indebted to the Moravians who had brought him to his understanding of Luther’s teaching. Preaching on Salvation by Faith in St Mary’s, Oxford, a fortnight after his Aldersgate heart-warming, Wesley praised Luther as ‘that man of God’ for his courage in preaching this doctrine in the face of opposition. He and Charles regularly worshipped and attended Moravian meetings in the Fetter Lane Society. Yet within a couple of years John had found (or thought he had found) serious flaws in Luther’s teaching and was breaking his connections with the Moravians, whose interpretation of Luther was extreme. Some of them thought that since salvation depended only on faith, not good works, they could behave without any moral constraints at all as everything would be forgiven. (There is some evidence that the chief scandal in the Fetter Lane Society was wife-swapping.) Wesley wrestled in vain to persuade them differently and eventually gave up on them and opened his own meeting house at the Foundry.

Though Wesley did not blame Luther for the excesses of the Moravians, he certainly saw Luther as the source of their error. He records in his Journal in June 1741 that he was somewhat embarrassed that, after recommending Luther’s commentary on Galatians, he had found when he read it

But what shall I say, now I judge for myself? Now I see with my own eyes? Why, not only that the author ... is quite shallow in his remarks on many passages, and muddy and confused almost on all; but that he is deeply tinctured with Mysticism throughout, and hence often dangerously wrong ... How blasphemously does he speak of good works and of the Law of God; constantly coupling the Law with sin, death, hell, or the devil; and teaching, that Christ delivers us from them all alike. Whereas, it can no more be proved by Scripture that Christ delivers us from the Law of God, than that he delivers us from holiness or from heaven. Here (l apprehend) is the real spring of the grand error of the Moravians. They follow Luther, for better for worse. Hence their "No works; no Law; no commandments." — Journal, June 15-16 1741

Wesley believed that Luther was fundamentally mistaken in his understanding of holiness:

Who has wrote more ably than Martin Luther on justification by faith alone? And who was more ignorant of the doctrine of sanctification, or more confused in his conceptions of it? In order to be thoroughly convinced of this, of his total ignorance with regard to sanctification, there needs no more than to read over, without prejudice, his celebrated comment on the Epistle to the Galatians. — Sermon CXII ‘On God’s Vineyard’

It has to be said that Wesley was very unfair to Luther. He was too blinded by his own outrage at the Moravians to see that Luther very explicitly condemned the idea that faith makes good works redundant. Luther plainly taught that those who have been justified by faith need no law only because they will always strive to do what God approves. It was what Wesley himself taught. Unfortunately Luther himself was not a very convincing example of the goodness and gentleness he commended, and his focus on faith alone as necessary for salvation was easily misinterpreted or used as an excuse by those who wanted to evade moral responsibility. Wesley rightly perceived that salvation cannot depend solely on believing that Christ has saved you: there must be inward and outward change as well. The key difference between Wesley and Luther was that for Luther love was subordinate to faith whereas for Wesley faith was only ‘the handmaid of love’: the former stressed justification, the latter sanctification.

It was not only Luther’s teaching about holiness that disappointed Wesley: it was Luther’s own lack of it. Luther was brutal in his abusive rudeness to those who disagreed with him and libellous in his attacks, calling the Pope, for example,‘ a vicar of the devil, an enemy of God, an adversary of Christ ... an arch-thief and robber.’

Worse still was Luther’s rabid antisemitism. In the early part of his career he wrote sympathetically about Jews, recognising Jesus’s Jewishness and arguing that if Jews were less harshly treated there was more hope of their conversion.

If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles ... When we are inclined to boast of our position [as Christians] we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ.

Later, however, when Jews fail to convert to his evangelical faith, his attitude hardened and his hatred of the people he blamed for rejecting the Messiah was expressed both in actions and in writing. He supported and promoted the expulsion of Jews from Saxony, then in 1543 published On the Jews and Their Lies, in which he describes Jews as a ‘base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth’ and ‘useless, evil pernicious people, such blasphemous enemies of God.’

After a lengthy diatribe, full of vitriolic accusation expressed in the vilest of language, he concludes by calling on Christians to set fire to their synagogues or schools, destroy their houses, take away all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, forbid their rabbis to teach, completely abolish their safe conduct on roads, prohibit them from money-lending, take away all their money, and force them to earn their bread by physical labour.

Luther’s antisemitism shaped German thought for the next 400 years and the tract itself resurfaced in the Nazi rallies at Nuremberg. Luther cannot escape some responsibility for spreading a hatred that eventually came to fruition in the Holocaust. Some Lutheran Churches have acknowledged this and repudiated this part of his legacy.

Both Luther and John Wesley were strongly opinionated and determined never to lose an argument. Yet there was a world of difference between Luther’s loveless coarseness and Wesley’s graciousness. If Luther had had a Twitter account he would have out-Trumped Trump.

Wesley wrote in his journal:

Wednesday, July 19 [1749] – I finished the translation of Martin Luther’s Life. Doubtless he was a man highly favoured of God and a blessed instrument in His hand. But oh! what pity that he had no faithful friend! None that would, at all hazards, rebuke him plainly and sharply, for his rough, intractable spirit, and bitter zeal for opinions, so greatly obstructive of the work of God!

John Wesley himself was much criticised for his doctrine of Christian Holiness and its presumption that human beings could ever be made perfect. His response was that he was asking no more than what every Church of England clergyman prayed at the start of every communion service:

... cleanse the thoughts of our hearts ... that we may perfectly love Thee ...

Nearly every time we sing a Wesley hymn we pray that same prayer, for it is the most recurrent theme in brother Charles’s hymns.

8. Scripture and Other Authorities

Most Methodists would find it nearly impossible to be Roman

Catholics if only because members of the Catholic Church have a duty to accept

unquestioningly and humbly the Church’s teaching as given by divine authority.

This teaching or ‘Magisterium’ has evolved since the time of Christ and

encompasses the Bible, traditional interpretations of it, decisions of church

councils, the historic creeds, the pronouncements of popes, and the consensus

of views of bishops and theologians over the centuries. What has been revealed

in scripture is interpreted, applied and supplemented by reason. The chief

architects of Catholic theology, the greatest theological thinkers, were the 5th century North African St Augustine, and the 13th century Italian

Thomas Aquinas, both of whom were philosophers as well as theologians. Both

were themselves greatly indebted to the pre-Christian Greek philosopher

Aristotle, whose thinking, especially about ethics, has always been deeply

influential in Catholic thought.

Most Methodists would find it nearly impossible to be Roman

Catholics if only because members of the Catholic Church have a duty to accept

unquestioningly and humbly the Church’s teaching as given by divine authority.

This teaching or ‘Magisterium’ has evolved since the time of Christ and

encompasses the Bible, traditional interpretations of it, decisions of church

councils, the historic creeds, the pronouncements of popes, and the consensus

of views of bishops and theologians over the centuries. What has been revealed

in scripture is interpreted, applied and supplemented by reason. The chief

architects of Catholic theology, the greatest theological thinkers, were the 5th century North African St Augustine, and the 13th century Italian

Thomas Aquinas, both of whom were philosophers as well as theologians. Both

were themselves greatly indebted to the pre-Christian Greek philosopher

Aristotle, whose thinking, especially about ethics, has always been deeply

influential in Catholic thought.

Martin Luther started out as an obedient Catholic and never entirely shook off the theological outlook formed in him when he was an Augustinian friar. Absolutely fundamental to his thinking and outlook was Augustine’s understanding of the total corruption of human nature by the Original Sin which brought about Adam’s Fall and which we all supposedly inherit. Where Luther broke away from the tradition was in coming to believe that, because human reason is corrupted by the Fall, all of the Magisterium that depends on reason is liable to the same corruption. Tradition, the decisions of councils, bishops and popes and the reasonings of philosophers are all alike questionable. There is one source of truth only on which can rely—God’s own word revealed in scripture.

Reason is a whore, the greatest enemy that faith has; it never comes to the aid of spiritual things, but more frequently than not struggles against the divine Word, treating with contempt all that emanates from God.

That is typical of the sort of over-the-top condemnation of reason that Luther so often came up with. Yet his view was far from consistent. He recognised that reason is a God-given gift to humanity which we must use in our ordinary everyday life and in relation to the things of this world. It was in relation to salvation that he ruled out reason, for he was convinced that noone comes to salvation through reasoned argument any more than they can earn their salvation by doing good works.

John Wesley agreed with Luther to some degree. He too believed in Original Sin and that the only remedy was the divine grace received by faith. He agreed that Scripture was the primary authority and that human reason cannot be entirely trusted. Yet there were significant ways in which Wesley differed from Luther in the matter of where authority lay and how we discover God’s will. For one thing, Wesley was not as pessimistic as Luther about the natural state of corruption and helplessness of human beings. Wesley believed that infant baptism washed away Original Sin and gave the infant a new start. The image of God is never completely erased in anyone and the divine likeness can be restored. He thought Luther was wrong to disparage reason. It is a divine gift to be used in the interpretation and application of the scriptures, as it has been by real Christians down through the ages. Wesley valued highly the teachings of the early Fathers of the Church, and was much more positive about tradition than Luther. He would have regarded with disdain a modern-day wilfully blinkered fundamentalism that relies on scripture alone and rejects science where it disagrees with the Bible. Nor would he have had much sympathy, I think, with more erudite but essentially bigoted schools of modern theology, like the neo-orthodoxy of followers of Karl Barth, that tend to view the Jewish/Christian scriptures as effectively the only channel through which the Holy Spirit conveys truth.

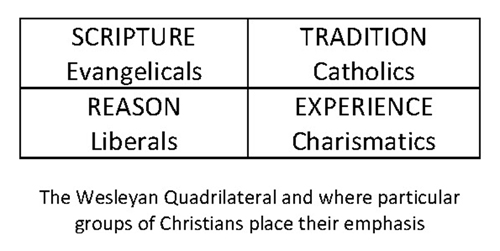

A 20th cent American Methodist scholar, Albert Outler, invented the term ‘the Wesleyan Quadrilateral’ to describe John Wesley’s understanding of the four sources of Christian authority, namely Scripture, Tradition, Reason and Experience. Wesley built on a foundation laid by an earlier Anglican divine, Richard Hooker, who had taught the first three of these as the basis for Anglican theology. They form a sequence.

What Scripture doth plainly deliver, to that first place both of credit and obedience is due; the next whereunto is whatsoever any man can necessarily conclude by force of reason; after these the voice of the Church succeedeth. - Hooker

According to Hooker, to discover truth you first turn to scripture, and if you find your answer you need look no further. If scripture does not provide an answer you turn to reason and then to the Church’s traditional teachings. Wesley gave a higher status to Tradition than Hooker did, and what he added to these was Experience, by which he meant the living witness of the Holy Spirit within, found in the voice of conscience and in answer to prayer. The term ‘Quadrilateral’ has been criticised as seeming to suggest that all four authorities are equally important whereas for Wesley, as for Hooker, Scripture far outranked the others.

The Wesleys valued scripture quite as highly as Luther; indeed, one might say they valued it more. Luther was very selective about the scriptures he used. He paid little attention to much of the Old Testament apart from the Psalms, treated Romans as the core text, and would gladly have expunged Esther and James altogether. John and Charles Wesley, by contrast, regarded the whole Bible as authoritative, quoted extensively from all of it, and were particularly fond of 1 John and Galatians.

Can Methodism today follow either Luther or the Wesleys uncritically in this matter of authority? I don’t think we can. Luther lived before the Enlightenment, and the Wesleyslived in its earliest phase before the development of modern understandings of historical and literary methods, and before the advent of psychology, sociology and scientific medicine. Their world view was one in which storms and earthquakes, disease and calamity could be attributed to divine wrath or evil spirits with only a very limited understanding of natural causes. Their simplistic and uncritical view of the Bible is no longer tenable in the light of modern understandings of how, why and when its books came to be written. Scripture—or at least some of it— is still of great inspirational value, an indispensable source of moral guidance and the only source of information about the life and teachings of Christ, whom we regard as the supreme revealer and revelation of God. It must still be central to our worship and to the shaping of our theology. In practice, though, it now takes a place alongside Tradition, Reason and Experience and sometimes has to take an inferior place to them. For example, whatever the Bible may say, we have long since abandoned slavery and the burning of witches; capital punishment is outlawed in civilised countries; we have come to accept that there is a patriarchal bias in much of scripture and tradition which has for too long prevented women from holding an equal place with men in the Church’s ministries. Although scriptural authority is still invoked to bolster a position or an argument, not even the most ardent fundamentalists are able to do it consistently and rationally because they have already conceded that there are scriptural commands that they will under no circumstances obey.

To be sure, Methodists are not agreed on the authority of scripture. There is a wide spectrum of views both on its authority and on its usefulness. The Methodist Church does not impose any single view on its members or on its preachers. Nor does it insist on the Wesleyan Quadrilateral except as a useful guide or framework for thinking in the round about any matter under debate. When a committee of the Methodist Conference produces a report or paper for discussion on an ethical, social or doctrinal matter it will typically review the relevant biblical teaching and the traditional theological considerations, and then proceed to evaluate the pros and cons of different points of view, drawing upon experience and reason in the widest sense before coming to conclusions. Essentially it is reason that now heads the Quadrilateral.

The Deed of Union which provided the legal basis for the reuniting of the various branches of Methodism in 1932 acknowledged the value of tradition and scripture without committing Methodists to any sort of

The Methodist Church claims and cherishes its place in the Holy Catholic Church which is in the Body of Christ. It rejoices in the inheritance of the Apostolic Faith, and loyally accepts the fundamental principles of the historic creeds and of the Protestant Reformation ... The Doctrines of the Evangelical Faith which Methodism has held from the beginning and still holds, are based upon the Divine Revelation recorded in the Holy Scriptures. The Methodist Church acknowledges this revelation as the supreme rule of faith and practice.

The principles of the Reformation and the ‘Revelation recorded in the Holy Scriptures’ inform our doctrine; they do not determine it absolutely; they are not the only sources to which we turn. Yet they are not dispensable, because we can only keep our place within ‘the Holy Catholic Church which is the Body of Christ’ if we retain enough communality of belief and practice with Christians in other Churches for us to recognise one another as members of one body. We certainly cannot lose Christ and still call ourselves Christians. The biggest offence of Luther from a Catholic point of view is that he split the undivided Church, which shattered into a thousand fragments over the next four centuries. John Wesley split the Church of England too, though very reluctantly and against his will. It has taken centuries to bring fragmented Methodism together again, and a century of ecumenical effort to break down the suspicions and hostilities that have separated denominations, to heal wounds and reunite separated Christians. There is still a long way to go.

9. The Lutheran Legacy

Approximately

2.4 billion people in the world are Christians, half of whom are Catholics,

about a third Protestants, and the rest Orthodox or other. Eamon Duffy has

characterised the Catholic-Protestant divide as ‘the warm south versus the cold

north, wine drinkers versus beer drinkers’! It is true that Lutheranism made its greatest impact in Northern Germany

and the Nordic countries—Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland—in which

it is today the established church. It is prominent too in the Netherlands,

Estonia and Latvia. Nevertheless, only half of the world’s Lutherans live in

Europe; the rest are spread through the USA, Africa, Asia and South America.

Approximately

2.4 billion people in the world are Christians, half of whom are Catholics,

about a third Protestants, and the rest Orthodox or other. Eamon Duffy has